*Tell us a little about yourself, your family, including how you got started as a journalist?

I was born in Split in 1956. My parents, both Dalmatians, already lived in Zagreb at the time, but my mother gave birth to me in Split, where there were all her relatives who could help her with a small child.

Ever since elementary school, and especially the beginning of high school, I have read a lot of literary texts but also newspapers, and political texts and cultural topics. I studied and graduated in comparative literature and philosophy at the Faculty of Philosophy in Zagreb. I published my first articles in a student newspaper in 1976, writing mostly about film. Even then, in the 80s, it was not easy to find a job. I was most attracted to books, I also enrolled in postgraduate studies in literature. However, at the end of 1980, a competition for young journalists appeared in Večernji list, I passed the competition filter and started working for Večernji list.

*Your professional work…

I fell in love with journalism. Like other beginners, I also wrote first in the city newsroom. After serving in the army, for a while I was the editor of the city column in the morning Zagreb edition, which was sold in Zagreb, just before noon and in the afternoon, in 60-70 thousand copies. These are very large numbers compared to today’s circulations in Croatia.

Later, I wrote about domestic politics, wrote topics and comments on the most important political topics. In the second half of the 1980s, writing became freer, and this was a period in which there was more journalistic freedom in the mainstream media in Croatia than in the 1990s under President Franjo Tudjman.

As a journalist, I was present at the session of the Presidency of the Croatian Communists when, in December 1989, a historic decision was made to organize the first multi-party elections in Croatia. I thought and hoped that real democracy would come to us as well. But no, the war came first.

With Stipe Mesic, Croatian president (2000-2010) at the reception for journalists in a year 2010

*You started your work in Vecernji list in 1981, it was still the time of the “old Yugoslavia”. How it was to be a journalist in the former Yugoslavia? The country was a Communist, or better to say a Socialist country, that was independent from the East bloc.

Journalism was freer in the 1980s in Yugoslavia and Croatia than in some previous decades. And it was not the same in all the republics of Yugoslavia. Of course, the media was noticeably freer than in the Eastern Bloc countries. Back then, journalism was an elite business in society. There were fewer journalists than today and their work was more appreciated than today.

It is said that during the former system, writing was smarter but more boring, and today more interesting but stupider. Simplification and generalization are wittily worded, but there are some truths in that assessment.

*Was in that time important to be a member in the Communist party for a position in the media?

It was important to be a member because all the editors-in-chief of the most important media were members of the Party until the one-party system collapsed. But in the 80s, writing and reporting was freer and more critical than before. In Vecernji list, which was by far the highest-circulation daily in Croatia, the vast majority of journalists were not in the Communist Party. After Tito’s death, the Party’s influence weakened throughout society, and when regimes in Eastern Europe began to fall and the Berlin Wall was torn down, it was clear that the Yugoslav political system was counting down the last days.

Luka Bebic, president od the Parliament, Ivo Josipovic, president od the Republic and me at 100th celibration of HND

*What was the relation with journalists from other parts of the country, with journalists outside Croatia (Croatia was till 1991 a republic in Yugoslavia)?

We were interconnected through the professional association of journalists of Yugoslavia, which was composed of national (republic) journalistic professional organizations. Numerous round tables were organized, various sports meetings of journalists, journalistic ski gatherings, etc. Journalists travelled a lot all over Yugoslavia, so we got to know each other.

*Did you feel hate between journalists from different part of Yugoslavia in 80´?

Until the second half of the 80’s, our mutual relations were good and correct. Serious tensions in society intensified with bad interethnic relations in Kosovo and the rise of Slobodan Milosevic from 1987 onwards. As is usually the case, the war of the early 1990s was prepared in the media. It started from the Serbian media controlled by Milosevic. There were a lot of inflammatory texts, the journalists who wrote them attacked not only politicians but also other journalists who had different views from theirs. This media war between journalists was not necessarily a war between journalists from different republics but a general intolerant showdown with dissidents nad „enemies“.

*It was the time with no mobile phones, no laptops, no tablets. How it was to work as a journalist?

Reporters were not sitting in the newsroom, which is the most common case today, but conducted interviews in the field. There were many more reportages than today. We received sets of 4-5 daily newspapers every day and we read, looking for incentives for texts and so on. To prepare the texts, we used to go to the journalistic documentation and photocopied everything we needed for the text. Today, these searches are performed by Google.

We dictated the reports from the outside with fixed telephone lines to typists. Yes, in that infrastructural sense, it was harder to work than it is today. But one journalist was producing less articles than today. Today, it is normal for a journalist to write and publish something every day. Then – that was not the case.

*What changed in the work in your newsroom with the independency of Croatia, but also with the war in Croatia 1991-1995?

In the early autumn of 1991, the editorial office of Večernji list was temporary transformed. I was a member of one of the two desk editor teams. Each team worked all day, meaning from 10 a.m. to midnight. But – the next day they were free. This was more rational because air raids were announced in Zagreb daily as well. Otherwise, wartime is usually not suitable for either quality or objective journalism. But many journalists respected all ethical journalistic standards and as much as they could, they wrote freely and independently.

And in the first half of the 90’s there were several completely free media – from the dailies it was a short time Slobodna Dalmacija, then Novi list, the legendary weekly Feral Tribune, anti-war Arkzin, Radio 101, Globus…

Journalists’ demonstrations in 2008

*You changed in one moment the company and the media owner. You started to work for a competition newspaper on the market, Jutarnji list. What was the difference in the work in Vecernji and Jutarnji?

I left Večernji list in January 1997 and started to work in a new weekly which called Tjednik. The founder was Slavko Goldstein and Krsto Cviić the first editor-in-chief. Večernji list was a great newspaper but in it I hadn’t enough freedom to write what I wanted to write. Tjednik was a big challenge with idea to be the first newsmagazine in Croatia. But in very short time, Tjednik changed its owner. Jutarnji list, the first new daily newspaper in Croatia in 50 years, was on the horizon. Jutarnji list was started by a young team of editors and journalists, then within Europa press holding (today Hanza media), which then had 15-20 other editions, but not daily newspapers. I come in Jutarnji list to its start. We were enthusiasts.

When we published at the end of 1998 the article that the wife of President Franjo Tudjman had deposited in a bank a very large amount of foreign currency, and Franjo Tudjman, declaring the property, claimed that she had no movables or real estate – then Jutarnji’s circulation reached 100,000 copies and was constantly growing.

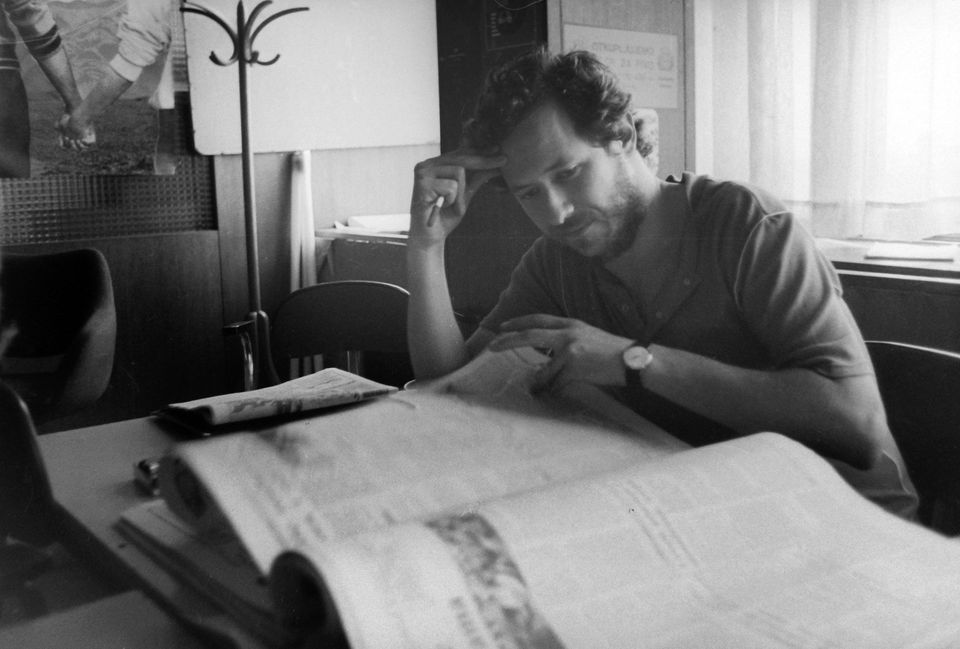

In Vecernji list newsroom in 80s

*Then you worked for Novi list, what is a local newspaper from Rijeka, but present in many parts of Croatia. How you see the role of local and regional media in Croatia?

I have been in Novi list for the last 14 years, since 2006. In that period I was the president of the Croatian Journalists’ Association for almost eight years. Novi list has been owned by a few dozen of journalists since the early 1990s and then they sold it in 2008 and it was later resold twice times. In the period from 1993 until the appearance of Jutarnji list in 1998, it was by far the freest daily newspaper in the country. Then the chance to become a national daily may have been missed. Classic local and regional media are important everywhere, but in the age of portals and social networks they play a smaller role than before.

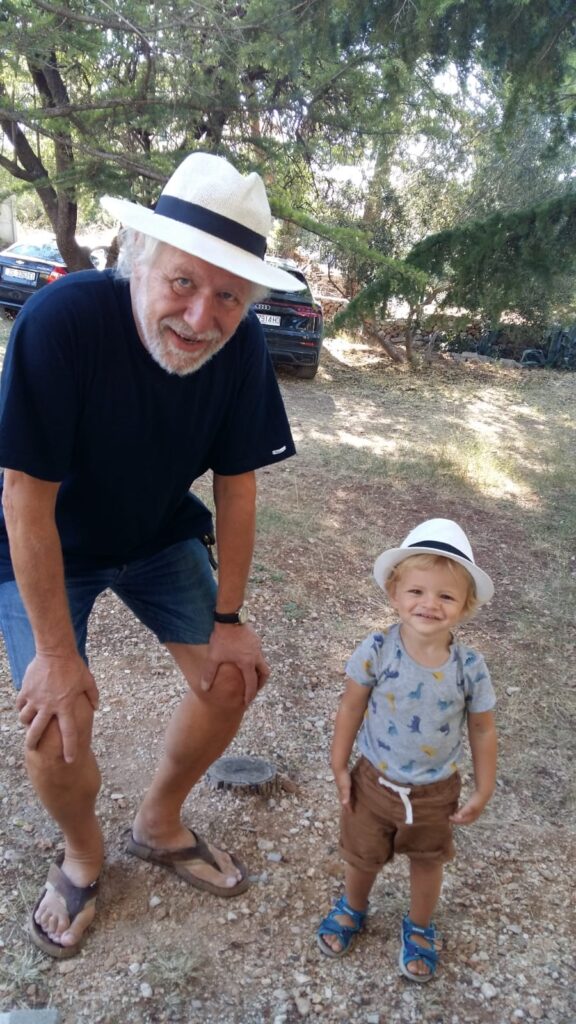

With my grandson Val

Zdenko Duka

*For a long period you had the position of the president of the Croatian Journalists Association (HND). Was it hard to be the chief of the leading journalists association in your country?

It was an honour for me to be two times elected leader of an organization that had more than 3.000 Croatian journalists. I tried to be constantly available to everyone’ call and to follow everything that happens regarding the media so that I can promptly respond to violations of freedom of journalists and media. It was a time of economic crisis when many journalists even lost their jobs. In short, we could say that we fought for ethics and freedom of public expression, we tried to preserve the reputation of the profession, we did everything to protect journalists from physical attacks and numerous threats. And to protect journalists from the arbitrariness of publishers, also.

*What was your biggest challenge in your work?

It was a time when the political authorities no longer put so much pressure on the media, but the pressure often came from media owners who wanted the media to be tools in some of their particular interests instead of in the public interest. We managed to establish editorial councils in the newsrooms to protect journalistic independence. We managed to get the media statutes into the media law, according to which journalists had power to refuse management’s proposals when appointing the editor-in-chief or when he wants to dismiss him.

*How you see the media situation in Croatia today?

The situation is not satisfying. In general, the print media has always been the most analytical. The ones that can mostly be said to be watchdogs of democracy in one country. However, as in many other countries, the circulation of the print media has been declining almost constantly, and the influence of newspapers is weak. The television market is quite developed, portals are becoming more influential. But most journalists are in a social worse position than they were 10 or 20 years ago.

But, it cannot be said that there is a distinct political control over the media now, there were certainly worse periods.

*How hard it was to stay always professional as journalists?

Unethical behavior in journalism, as well, sometimes brings short-term benefits, better status, higher salary. But when your editors and all others know that you have firm principles and that you will not give in, then they all leave you alone and do not pressure you to do something journalistically incorrect. There is no true journalism without correctness and respect for professional rules.

*How important is the work of SEEMO as a press freedom organisation?

SEEMO is one of the most important organizations for the promotion and protection of media and journalistic freedoms in Europe, and especially important for this region of Central and Southeast Europe. Because, in addition to the protection of media freedom, it also has a function of mutual rapprochement and respect, after the bloody wars of the 1990s in the former Yugoslavia.

I think that in 20 years SEEMO really did a lot for the freedom of the media and journalists and for tolerance. Ultimately, all journalists in the region have more or less the same or similar professional problems.

*Please walk us through a typical workday. How do you manage your time today?

I read a lot. Not only newspapers and portals but also literature, philosophy and political science and I watch many news television channels. For my journalistic work the most informative in our country is the N1 channel, which is a news channel throughout the day. Of the foreign news channels, I mostly follow BBC news, France 24, CNN, Al Jazeera.

I contact many professors, fellow journalists and politicians with whom I comment on various political and other events. It helps me when writing articles.

By the way, I have been retired since June, but I still write a few commentary texts or interviews a month, mostly for the lupiga.com portal and some others.

Zdenko Duka

*Finally, as press freedom, human rights and democracy are very important in your life, can you give please some advice for younger journalists?

Journalism is a specific job and its basic meaning is information in the interest of the public. Well-informed individual can more easily make decisions about his life, both private and public, he can be a free and critical participant in social and political life. My message to young journalists is that a journalist should never allow himself to be bought in any way for anyone’s interest. He has to have a passion for truth, exposing corruption, courage and credibility to make society better.